Funeral programs share compelling stories of lives and communities across a century and are a treasure for families, genealogists, and learners of all ages. Access the collection at dlg.usg.edu/collection/aarl_afpc.

Over 11,500 pages of digitized African American funeral programs from Atlanta and the Southeast are now freely available in the Digital Library of Georgia. The collection of 3,348 individual programs date between 1886-2019.

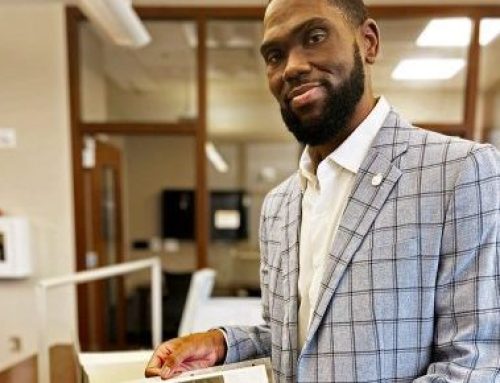

“Funerals are such an important space for African Americans,” said Derek Mosley, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History archivist and lead project contributor. “The tradition of funerals is not reserved for the wealthy or privileged, but the community. It is that lasting document of someone’s life. In the program is the history, and throughout this collection you see the evolution of the stories people left for future generations. I was amazed at the one-pagers from the 1940s, and by the 2000s there were full color, multiple pages, and photographs highlighting the life and love shared by the families. This collection is public space for legacy.”

One of the programs that he found powerful was for Judge Austin Thomas Walden, the first Black municipal judge in Georgia since the Reconstruction era. He also served in World War I as an infantryman and held many leadership positions in Georgia, including with the NAACP. His 1965 benediction was given by the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr.

He became a founder and co-chairman of the Atlanta Negro Voters League. His election in 1962 to membership on the State Democratic Committee of Georgia and his appointment by Governor Carl E. Sanders as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1964 were firsts in Georgia for members of his race. Also, his appointment in 1964 by Mayor Ivan Allen as an Alternate Judge of the Municipal Courts of Atlanta was the first such appointment in Georgia and the South since the days of Reconstruction. – from the funeral program of Judge Austin Thomas Walden

Documenting both urban and rural areas, the collection provides important information for genealogical research and for understanding African American life during different time periods. For example, you can read how some families migrated North to cities like Chicago and New York to pursue job opportunities. Some programs document 20 or more names in one family or in a small town, including elders in a community.

Funeral programs provide valuable social and genealogical information, typically including a photograph of the individual, an obituary, a list of surviving relatives, and the order of service. Some programs provide more extensive genealogical information such as birth and death dates, maiden names, past residences, and place of burial. This data can otherwise be hard to find, particularly for marginalized populations. The records of many in these communities were often either destroyed, kept in private hands, or never created in the first place.

“The challenge for African American genealogy and family research continues to be the lack of free access to historical information that can enable us to tell the stories of those who have come before us,” said Tammy Ozier, president of the Atlanta Chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society. “This monumental collection helps to close this gap, allowing family researchers to get closer to their clans, especially those in the metro Atlanta area, the state of Georgia, and even those outside of the state.”

The Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History began collecting funeral programs in 1994 with an initial donation by library staff. Since then, staff and the public have continued to add to the collection with a focus on the city of Atlanta. Although the materials have been physically open for research for decades, they can now be accessed beyond the library’s walls.

“I hope people will take time to read what is possibly the only account of an individual’s life and learn not only about them, but their community, the churches they served in, the work they did, and the accomplishments they made to make their small piece of the world a better place,” said Tamika Strong, archivist with the Georgia Archives. “In learning about the person, you’re learning about the community.”

For Strong, the programs are personal.

“Through this collection, I learned about my uncle who died when he was 15,” she said. “I grew up hearing stories about him. He was smart as a whip and never complained about his long-term illness. He died suddenly just two days before his high school graduation. His legacy will live on as a part of this collection, and we will share with the next generation.”

He was a quiet easy going young man, and to know him was to love him, and through all of his sickness, he never complained. After his lengthy illness he quietly slipped away in the Georgia Baptist Hospital May 27, 1970.

– from the funeral program for Stanley Maddox

The collection contains contributions from the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, a special library of the Fulton County Library System; the Wesley Chapel Genealogy Group; and the Atlanta Chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society. Digitization was funded by Georgia Public Library Service’s Archival Services and Digital Initiatives.

Georgia Public Library Service (GPLS) leads the digitization of historical materials held by public libraries around Georgia, including the African American funeral program collection, to enable educators and students of all ages to tell the story of their community. Thanks to a robust partnership with the Digital Library of Georgia, these digitized collections are displayed and searchable within their online portal. GPLS previously led the digitization of over 7,700 African American funeral programs from the Augusta-Richmond County and the Thomas County public library systems.

“Georgia Public Library Service is committed to inclusiveness, ensuring service to underserved communities, and showcasing the diversity and history that make Georgia special,” said Angela Stanley, director of GPLS’s Archival Services and Digital Initiatives.

She believes that those who view the collection will find stories both personal and universal, such as the program for Ethel Carter Thompson Poole. Better known as “Ma Poole,” Mrs. Poole’s obituary not only tells of her keen sense of humor and love of chocolate chip cookies, but also of her moves between various South Carolina counties – information that can be crucial for genealogical research.

The programs also reveal stories of personal triumphs. Mary Catherine Allen was only 39 years old when she passed away in 1973, but during her career became the first Black woman to hold the position of assistant underwriter at the Atlanta Branch of the Continental Insurance Company. Harmon Griggs Perry was an “award-winning photojournalist and writer chronicling African American life in Atlanta” and helped to found the Atlanta Association of Black Journalists.

Mr. Perry made history in 1968 when he became the first Black reporter to be hired by The Atlanta Journal. His first assignment for The Journal was covering the assassination and funeral of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. After leaving the paper in 1973, he became Southeastern Bureau Chief for Jet magazine and later returned to freelancing. He devoted his career to telling the stories of Black people from all walks of life.

Funeral programs are still being accepted; to contribute to either collection, contact the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History or the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society Atlanta Chapter.

Learn more about historical collections through Georgia’s public libraries at georgialibraries.org/genealogy.