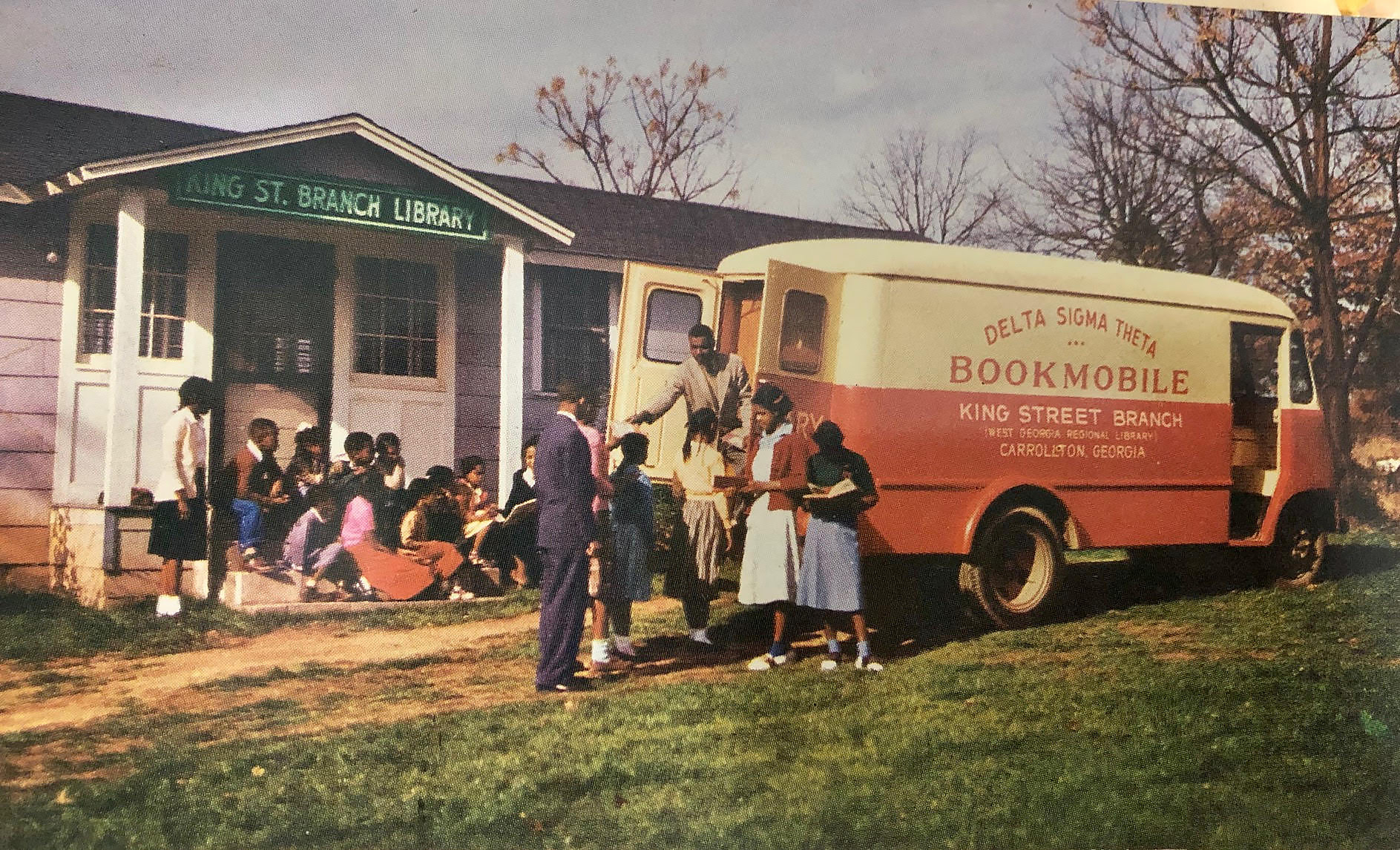

To better serve the region’s rural, poor population, Mr. Childs drove the bookmobile to nine segregated schools and six communities across five counties each month. (Courtesy of Childs family)

LeRoy Childs’ vision to broaden access to library services brought him state and national recognition. He also was Georgia’s first black library director. Childs died in 1986 at age 63.

LeRoy Childs lived with purpose, with a mission to establish the library as a place for lifelong learning, a place to even the playing field for those who lacked access to formal education. He pursued this goal through his leadership at West Georgia Regional Library and in the formation of state and national library policy.

“He wanted public library service to be more accessible for everyone. He watched out for people who were poor; for those who lived on dirt roads off the beaten path,” said Roni Tewksbury, who worked with Childs from 1983-1986.

When Childs completed his bachelor’s degree in social sciences in 1947, a resident of Bowdon, Georgia (population 1,100 in 1950), offered him and his wife, Vivian, free room

“He saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself – potential – and he motivated me to further my education.” – Jacine Harrison Mason

and board if they moved there from North Carolina to start a local school for the children of sharecroppers. Childs had never seen such poverty. He and his wife taught children in a barn, and even when they began to be paid a small salary, they spent it on clothing and other materials for the students.

Eventually, the school was moved into a building in nearby Carrollton (population 7,700 in 1950). In 1951, Childs was asked by Edith Foster, director of the West Georgia Regional Library, to be the branch and bookmobile librarian at the King Street Library, which served only African American residents of Carrollton due to segregation.

“I talked with Mr. Childs about what the assignment would mean: responsibilities, challenges, dedication, sacrifice – but all-in-all, the opportunity to enrich the lives of many people and to broaden his own horizons,” said Foster in her autobiography, “Yonder She Comes.”

The library had very little funding. Childs was the only staff member, and it was open to the public for two afternoons each week. To better serve the region’s rural, poor population, he also drove the bookmobile to nine segregated schools and six communities across five counties each month.

He recognized the lack of adult education opportunities for those in his community, and he sought to make the King Street Branch and bookmobile models that other small, rural libraries could follow.

Childs actively built community partnerships to strengthen adult education at the library by working with organizations such as the American Red Cross, Public Health Department, the Carroll County Chapter of the Mental Health Association, and many more. He offered these groups library space and services and was deeply involved in developing and promoting their programming, even selecting and purchasing books for the library tailored to their curriculum.

His commitment to bringing adult education opportunities to his community was deep. For example, he partnered with a group to train local Korean and World War II veterans in agriculture. Most of the veterans had a very basic reading level, if they were literate at all. None had the opportunity to complete high school. Childs went with the agricultural instructor to veteran homes to assess their reading and then acquire tailored materials to strengthen literacy.

He detailed these efforts in his 1960 thesis at Clark Atlanta University, where he attained his Master of Science in Library Service.

Childs wrote: “These programs were generally successful and added to the educational well-being of the persons who participated. The branch library in the meantime gained new friends and patrons.”

His career grew at West Georgia Regional Library, and he was eventually named director in 1976. His reputation for ideas to improve library service gained recognition at a national level.

For many years he served as 6th District public library representative, working with colleagues in Washington, D.C., to obtain substantial funds to support libraries. He was appointed by Gov. Joe Frank Harris to the Georgia Committee on the White House Conference of Libraries, a position that took him to both Washington, D.C., and to Georgia’s Capitol to promote his ideas. He held many other statewide offices as well.

“He had the respect of all the people including the governor. Legislators always had their doors open for him,” said former Library Director Edith Foster.

He also had the respect of his staff at West Georgia Regional Library, where he served as mentor and teacher to many.

“He always had our best interest at heart,” said Jacine Harrison Mason. Childs hired her as a library memory typewriter operator at age 17. “He saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself – potential – and he motivated me to further my education.”

Former staff describe him as a hands-on leader, willing to do whatever the job required.

“If he needed to help at the front desk checking out books, he would do it,” said Mason. “Or if he got a call that they needed his advice at the Capitol, he’d be out the door.”

In 1967, the local libraries were desegregated. The King Street Branch closed, and Neva Lomason Memorial Library became the location for all residents of Carrollton. Childs was assistant director of the library system at the time.

Roni Tewksbury remembers standing with Childs at the library’s window one morning afterward. They looked across to an adjacent cultural arts center, where overnight someone had painted racist graffiti on the windows.

“I told Mr. Childs, ‘I’ve never seen anything like that before,’” Tewksbury said. “He replied, ‘Then you haven’t lived.’”

“My grandfather believed that the library was for the person who doesn’t have the opportunity to go to college but wants to be a police officer or scientist. The library provides an opportunity to educate people who don’t have many opportunities in life.” – Jason Childs

Childs’ grandson, Jason, believes this was a teaching moment. “Racism was a distraction from what he was trying to accomplish,” he said. “He did not participate in the social construct of racism. By not participating, he was able to be elevated, to be above it.”

He was a trailblazer in his community and a part of many local organizations, and he advocated for years for a new library branch to serve Douglas County. In the summer of 1986, his advocacy came to fruition as that branch was opened.

“Mr. Childs worked so hard for that building but when I saw him at the celebration, I knew something was wrong,” said Roni Tewksbury. “He called me the next Monday morning to say ‘I won’t be in this week, please take care of the library for me.’”

He died almost a week later from cancer; only his family and close friends knew of the illness.

His legacy remains strong, and in Carrollton, Georgia, many residents still speak highly of him 34 years after his death.

“He believed that the library is for the person who doesn’t have the opportunity to go to college but wants to be a police officer or scientist,” said Jason Childs. “The library provides an opportunity to educate people who don’t have many opportunities in life.”